What is an antigen? This exploration dives into the fascinating world of antigens, those molecular triggers that set our immune systems in motion. From their fundamental role in identifying foreign invaders to their critical role in vaccine development and medical diagnostics, antigens are essential components of our health. We’ll uncover their diverse structures, functions, and the intricate ways our bodies recognize and respond to them.

Antigens, essentially any molecule that can trigger an immune response, come in a variety of forms. Proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids all qualify, and each type plays a unique role in stimulating our immune system. Understanding their structure is crucial to comprehending how they work. Their specific shapes and the presence of unique binding sites determine their ability to activate our defenses.

This detailed analysis will unveil the intricate mechanisms behind antigen presentation, interaction with antibodies, and the factors influencing their immunogenicity.

Defining Antigens

Antigens are a crucial component of the immune system, playing a vital role in recognizing and responding to foreign invaders. Understanding their characteristics and classification is essential for grasping the intricacies of immune responses and disease mechanisms. This exploration delves into the specifics of antigens, outlining their definition, key characteristics, types, and roles in the body.Antigens are essentially any molecule that can trigger an immune response.

Crucially, this response is not random but highly specific, targeting particular antigens. What differentiates antigens from other molecules is their capacity to be recognized by the immune system’s specialized cells, like B cells and T cells. These cells possess unique receptors that bind to specific antigen structures, initiating a cascade of events leading to the elimination of the foreign substance.

Antigen Types

Antigens exhibit a diverse array of chemical compositions, with proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids all serving as potential triggers for immune responses. These molecules, often found on the surface of pathogens, are recognized by the immune system as foreign entities.

Antigens are essentially foreign invaders that trigger your immune system. Sometimes, these invaders are harmless, like certain foods, but other times, they can cause significant issues, like in cases of irritable bowel syndrome. Understanding how your body reacts to these antigens, especially in conditions like colonoscopy irritable bowel syndrome , is crucial for diagnosis and treatment. So, what are the different types of antigens, and how do they affect our health?

Classifying Antigens

The following table Artikels the major types of antigens based on their chemical composition and biological function.

| Antigen Type | Chemical Composition | Biological Function |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Antigens | Polypeptide chains composed of amino acids | Frequently found on the surface of pathogens, initiating a strong immune response. Examples include bacterial toxins and viral coat proteins. |

| Carbohydrate Antigens | Sugars, polysaccharides, and glycoproteins | Present on the surfaces of various pathogens, triggering immune responses, often in conjunction with protein antigens. Examples include bacterial capsule polysaccharides and blood group antigens. |

| Lipid Antigens | Fatty acids, phospholipids, and glycolipids | Can act as antigens, especially when combined with other molecules. They are often involved in the immune response to parasites or certain infections. |

Antigenic Determinants

Antigens aren’t uniform in structure; they possess specific regions called epitopes or antigenic determinants. These are the crucial parts of the antigen recognized by the immune system’s receptors. The unique shape and chemical composition of epitopes dictate the specificity of the immune response. Different antigens will have unique epitopes, allowing for a targeted response. The complexity of the antigen’s structure and the presence of multiple epitopes can lead to a more robust immune response.

Antigen Structure and Function

Antigens are crucial components in the immune system, acting as signals that trigger an immune response. Understanding their structure and function is vital to comprehending how the body defends itself against pathogens and foreign substances. Their molecular makeup, shape, and size all play key roles in this process. This section will delve into the specifics of antigen structure and its relationship to the immune response.Antigen structure dictates how the immune system recognizes and responds to it.

The unique arrangement of atoms within an antigen molecule determines its ability to bind to specific receptors on immune cells. This specific binding is fundamental to the immune response. The intricate details of this binding, involving molecular shapes and forces, are essential for effective immune recognition.

General Structure of Antigens

Antigens exhibit a diverse range of structures, reflecting their varied origins. They can be proteins, polysaccharides, lipids, or nucleic acids. The specific molecular makeup of an antigen is what ultimately determines its immunogenicity. Proteins, for example, are frequently potent antigens due to their complex three-dimensional structures and abundance of different amino acid sequences.

Relationship Between Antigen Structure and Function

The shape and specific chemical groups on the surface of an antigen, known as epitopes, are critical in initiating an immune response. Antigenic determinants, or epitopes, are the specific regions on the antigen that interact with immune receptors. The unique three-dimensional shape of an epitope is crucial for recognizing and binding to the corresponding receptors on immune cells, such as B cells and T cells.

This interaction triggers a cascade of events that lead to the elimination of the pathogen.

Importance of Antigen Shape and Specific Binding Sites

The specific three-dimensional structure of an antigen is vital for its function. The shape of an antigen determines which parts of it can bind to immune receptors. This specific binding is crucial for initiating the immune response. Antigens with similar shapes can sometimes trigger cross-reactivity, where the immune system mistakenly targets a harmless substance resembling a harmful one.

This can lead to autoimmune diseases.

Relationship Between Antigen Size and Immunogenicity

Larger antigens tend to be more immunogenic. This is because larger molecules often possess more epitopes, or antigenic determinants. More epitopes mean more potential sites for interaction with immune receptors, leading to a stronger immune response. Conversely, smaller molecules may not be recognized as effectively by the immune system, reducing their immunogenicity.

Comparison of Different Types of Antigens

| Type of Antigen | Molecular Makeup | Example | Immunogenicity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Antigens | Chains of amino acids folded into complex 3D structures | Antibodies, viral proteins | Generally high |

| Polysaccharide Antigens | Chains of monosaccharides | Bacterial capsules, some viral components | Can vary, sometimes requiring conjugation to be immunogenic |

| Lipid Antigens | Fatty acid chains and other hydrophobic molecules | Components of bacterial cell membranes | Often requires conjugation to be immunogenic |

| Nucleic Acid Antigens | DNA or RNA | Viral genomes, some bacterial components | Can be immunogenic, often as part of a complex |

Antigen Presentation

Antigen presentation is a crucial step in the adaptive immune response. It’s the process by which cells of the immune system display fragments of antigens to T cells, initiating a targeted immune attack against pathogens. This presentation allows T cells to recognize and respond to specific invaders, ensuring a tailored defense against infections.The immune system’s intricate network relies on antigen presentation for its effectiveness.

By showcasing these fragments, the immune system can effectively distinguish between harmful invaders and the body’s own healthy cells. This precise recognition is critical for avoiding harmful autoimmune reactions.

Antigen Processing by Antigen-Presenting Cells (APCs)

Antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as dendritic cells and macrophages, are specialized cells dedicated to capturing, processing, and presenting antigens. They act as messengers, communicating information about invading pathogens to T cells. This process ensures that the immune response is directed towards the specific threat.

Antigen Processing and Presentation to T Cells

The processing of antigens involves breaking down large proteins into smaller peptides. This crucial step is followed by the binding of these peptides to MHC molecules. This binding is a crucial step that allows the T cell receptor to recognize the presented antigen. The specific mechanisms are different for different types of antigens and APCs, reflecting the complexity of the immune response.

Role of MHC Molecules

Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules are integral to antigen presentation. They act as “flags,” displaying the processed antigen fragments on the surface of the APC. Different types of MHC molecules (MHC class I and MHC class II) present antigens to different types of T cells. MHC class I molecules present antigens to cytotoxic T cells, which directly kill infected cells.

MHC class II molecules present antigens to helper T cells, which orchestrate the immune response.

Step-by-Step Explanation of Antigen Processing and Presentation

- Capture and Uptake: APCs, like dendritic cells or macrophages, engulf pathogens or cellular debris containing antigens. This engulfment is a crucial initial step for triggering the subsequent immune response.

- Antigen Degradation: The engulfed material is broken down into smaller peptides inside the APC. Specialized enzymes within the APC degrade the antigen proteins into manageable fragments. This process is critical to make the antigen suitable for presentation.

- MHC Molecule Loading: The processed peptides are then loaded onto MHC molecules. This loading process is carefully orchestrated, with specific peptides binding to specific MHC molecules. This ensures accurate presentation of the antigen.

- Antigen Presentation: The MHC-peptide complex is then transported to the APC’s surface. Here, the complex is displayed for recognition by T cells.

- T Cell Recognition: T cells with T cell receptors (TCRs) specific to the presented antigen recognize and bind to the MHC-peptide complex on the APC surface. This interaction triggers the activation of the T cell.

Diagram of Antigen Presentation

(A detailed diagram of antigen presentation would be too complex to describe here without visual aids. Imagine a dendritic cell (or other APC) with a pathogen engulfed inside a vesicle. The pathogen’s proteins are being broken down into smaller peptides. These peptides are then binding to MHC class II molecules. The MHC-peptide complex is transported to the cell surface, where it is presented to a T cell that recognizes the specific peptide fragment. An arrow showing the movement of peptides from the internal vesicle to the surface would be a good visual aid.)

Antigen-Antibody Interactions

Antigen-antibody interactions are crucial for the body’s immune response. These interactions, characterized by high specificity and affinity, are the driving force behind the neutralization of pathogens, the activation of immune cells, and the elimination of harmful substances. Understanding these interactions is essential for comprehending how the immune system functions and developing treatments for various diseases.

Antigen-Antibody Binding

The binding of an antigen to an antibody is a highly specific and reversible process. Antibodies possess unique binding sites, or paratopes, that precisely recognize and bind to specific epitopes on the antigen surface. This interaction is akin to a lock-and-key mechanism, where the complementary shapes of the antigen and antibody determine the binding strength. The precise fit between the paratope and epitope ensures that the immune system targets the appropriate foreign invaders without harming the body’s own cells.

Specificity and Affinity of Interactions

Antigen-antibody interactions exhibit high specificity, meaning that a particular antibody binds only to its corresponding antigen. This specificity is crucial for targeted immune responses. Affinity refers to the strength of the individual interaction between a single antibody binding site and a single epitope. High affinity interactions are more stable and efficient in triggering the immune response. The overall binding strength, or avidity, is influenced by the number of binding sites and their individual affinities.

For example, antibodies with multiple binding sites can bind to multiple epitopes on a single antigen, increasing the avidity and overall stability of the interaction.

Different Types of Antigen-Antibody Interactions

Different types of antigen-antibody interactions exist, each with its unique characteristics and implications for the immune response. Neutralization, opsonization, agglutination, and precipitation are all examples of how antibodies can interact with antigens to eliminate pathogens or neutralize their effects.

Forces Involved in Antigen-Antibody Binding

Several forces contribute to the strength and specificity of antigen-antibody binding. These forces include:

- Hydrogen bonds: These weak bonds are essential for maintaining the precise fit between the paratope and epitope.

- Van der Waals forces: These attractive forces arise from temporary fluctuations in electron distribution. They contribute to the overall binding strength.

- Electrostatic interactions: Opposite charges attract, contributing to the binding affinity.

- Hydrophobic interactions: Non-polar regions of the antigen and antibody can interact, contributing to the overall binding energy.

Table of Antibody Interactions with Antigens

| Type of Interaction | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Neutralization | Antibodies block the harmful sites on a pathogen, preventing it from infecting cells. | Antibodies neutralizing toxins produced by bacteria. |

| Opsonization | Antibodies coat pathogens, making them more readily recognized and engulfed by phagocytic cells. | Antibodies coating bacteria, making them easier for macrophages to ingest. |

| Agglutination | Antibodies cross-link multiple antigens, forming large complexes that precipitate out of solution. | Antibodies causing clumping of bacteria, facilitating their removal. |

| Precipitation | Antibodies cross-link soluble antigens, forming insoluble complexes that precipitate out of solution. | Antibodies causing the precipitation of soluble toxins. |

Antigenicity and Immunogenicity

Understanding the intricacies of antigen interactions with the immune system is crucial for comprehending the mechanisms behind immunity. Antigenicity and immunogenicity are two closely related yet distinct concepts, both essential for an effective immune response. Antigenicity refers to the ability of a molecule to bind to an antibody or a T-cell receptor, while immunogenicity refers to the capacity of an antigen to stimulate an immune response.

This difference is fundamental in understanding how the body recognizes and responds to foreign substances.

Difference between Antigenicity and Immunogenicity

Antigenicity and immunogenicity are often confused. Antigenicity focuses on the antigen’s capacity to be recognized by the immune system, while immunogenicity focuses on its ability to induce an immune response. A molecule can be antigenic without being immunogenic. For example, a small molecule (hapten) might bind to a larger carrier protein (making it antigenic), but it may not trigger a full immune response on its own.

Conversely, a molecule might be immunogenic but not necessarily antigenic in a way that the immune system can directly recognize it.

Factors Influencing Immunogenicity

Several factors influence an antigen’s ability to trigger an immune response. The immunogenicity of an antigen depends on its ability to be recognized by the immune system and stimulate an immune response. The factors affecting this include size, complexity, and chemical composition.

Antigens are substances that trigger an immune response, like a body’s way of recognizing something foreign. Sometimes, this recognition can extend to people perceived as different, leading to the fear of strangers, or xenophobia. Learning about how our bodies react to antigens, including those associated with people who are perceived as different, is a crucial step to understanding how we can overcome negative biases and reactions like fear of strangers xenophobia.

Essentially, antigens are the key to understanding our immune system’s interaction with the world around us.

Antigen Size, Complexity, and Chemical Composition

The size of an antigen plays a significant role in its immunogenicity. Larger antigens tend to be more immunogenic than smaller ones. This is because larger molecules have more potential epitopes (antigenic determinants), the specific regions on the antigen recognized by the immune system. Antigen complexity also affects immunogenicity. More complex antigens, with diverse and intricate chemical structures, generally elicit stronger immune responses than simpler ones.

The chemical composition of an antigen is also crucial. Proteins are generally more immunogenic than carbohydrates or lipids. The presence of certain chemical groups or motifs can also significantly influence the antigen’s immunogenicity.

Antigens are basically anything your immune system recognizes as foreign, like a tiny intruder trying to sneak into your body. This recognition process is crucial, especially when dealing with conditions like having globus alongside IBS, where the immune system might be reacting in unusual ways. Having globus alongside IBS can involve a complex interplay of factors, and understanding antigens is key to comprehending how the immune system responds to these situations.

So, the next time you hear about antigens, think of them as the body’s early warning system, constantly on the lookout for troublemakers.

Highly and Less Immunogenic Antigens

Examples of highly immunogenic antigens include bacterial toxins, viral proteins, and transplanted tissues. These molecules often have a complex structure and diverse epitopes. On the other hand, simple molecules like small peptides or certain carbohydrates might be less immunogenic or even non-immunogenic. This is because they might not contain enough epitopes to stimulate a robust immune response.

For instance, certain polysaccharides might not trigger a significant immune response if they lack the proper chemical groups.

Steps in Determining Antigen Immunogenicity

- Isolate the antigen of interest.

- Inject the antigen into an appropriate animal model (e.g., mouse).

- Monitor the animal for signs of an immune response (e.g., antibody production). This can be measured through various immunological assays, including ELISA, or through direct observation of cellular responses.

- Quantify the immune response (e.g., antibody titer) using standardized techniques. Different assays can measure different aspects of the immune response.

- Analyze the results to determine the antigen’s immunogenicity based on the magnitude and type of immune response elicited. This often involves statistical analysis and comparison to control groups.

Antigen Recognition by the Immune System: What Is An Antigen

The immune system’s remarkable ability to defend the body against a vast array of pathogens relies on its sophisticated recognition of foreign invaders. This recognition process, fundamental to adaptive immunity, involves a highly specific interaction between the immune system’s components and unique molecular signatures on the surface of antigens. Understanding this intricate mechanism is crucial for comprehending how the body mounts effective defenses against infection.The immune system distinguishes between “self” and “non-self” through a complex network of receptors and signaling pathways.

These pathways identify and respond to antigens, which are essentially any molecule that can trigger an immune response. This recognition process is incredibly precise, allowing the immune system to target specific pathogens while minimizing harm to the body’s own tissues.

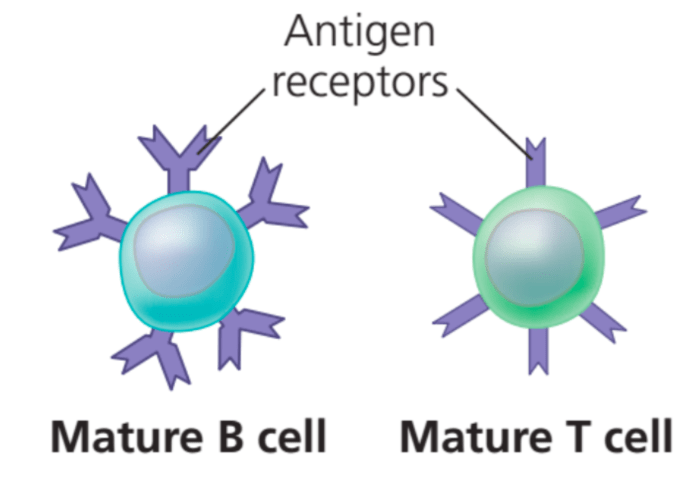

Lymphocytes and Antigen Recognition

Lymphocytes, a critical component of the adaptive immune system, are responsible for recognizing and responding to specific antigens. These cells, including B cells and T cells, possess unique receptors that can bind to a vast array of antigens. This remarkable diversity of receptors enables the immune system to respond to a multitude of pathogens, each with its unique molecular structure.

Clonal Selection and Expansion

The concept of clonal selection and expansion is central to the immune system’s ability to mount a targeted response to a specific antigen. When an antigen enters the body, it encounters a vast pool of lymphocytes. Only those lymphocytes with receptors that specifically bind to the antigen will be stimulated. This process is known as clonal selection, as it selects only the appropriate lymphocytes to respond.

These selected lymphocytes then undergo rapid proliferation, a process called clonal expansion, generating a large army of effector cells capable of eliminating the pathogen. This response ensures that a sufficient number of immune cells are available to combat the infection effectively.

Types of Immune Cells Involved in Antigen Recognition

The immune system employs a variety of specialized cells in the process of antigen recognition. B cells, for instance, are primarily involved in antibody-mediated immunity. Their receptors bind directly to antigens, marking them for destruction. T cells, on the other hand, play a crucial role in cell-mediated immunity. Helper T cells, in particular, are vital for coordinating the immune response, while cytotoxic T cells directly attack and destroy infected cells.

These different cell types work in concert to mount a comprehensive defense against pathogens.

- B Cells: These lymphocytes are crucial for antibody-mediated immunity. Their surface receptors, known as B cell receptors (BCRs), bind directly to antigens. This binding triggers a cascade of events leading to the production of antibodies, which neutralize pathogens and mark them for destruction by other immune cells.

- T Cells: T cells are essential for cell-mediated immunity. Their surface receptors, called T cell receptors (TCRs), recognize antigens presented on the surface of other cells. Helper T cells coordinate the immune response, while cytotoxic T cells directly attack and kill infected cells.

- Antigen-Presenting Cells (APCs): APCs, such as dendritic cells, macrophages, and B cells, play a vital role in presenting antigens to T cells. They engulf pathogens, process the antigens, and display them on their surface, enabling T cells to recognize and respond to the specific threat.

Visual Representation of Antigen Recognition

Imagine a complex puzzle with numerous pieces (antigens) and a set of specialized puzzle pieces (lymphocytes) that can fit only certain ones. An antigen enters the body, like a new piece in the puzzle. Specialized cells, like antigen-presenting cells, identify this piece and prepare it for presentation to the appropriate lymphocytes. These antigen-presenting cells display the antigen on their surface, allowing specific lymphocytes with matching receptors to bind.

This binding triggers the selection and expansion of these lymphocytes, producing a large number of effector cells that can effectively eliminate the pathogen, like finding all the matching pieces to complete the puzzle. The result is a highly targeted and effective immune response.

Applications of Antigens in Medicine

Antigens, those molecular flags that trigger immune responses, are crucial players in numerous medical applications. Their unique characteristics allow for precise targeting and manipulation of the immune system, leading to diagnostics, therapeutics, and groundbreaking research. Understanding how antigens interact with the immune system is key to harnessing their potential for improving human health.

Diagnostic Tests Using Antigens

Antigens play a vital role in diagnostic tests, particularly in detecting and quantifying specific substances or diseases. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) are prominent examples. In ELISA, antigens are strategically placed on a surface, and antibodies specific to the target antigen are added. The presence and amount of the target antigen can then be precisely measured by the bound antibody.

This allows for sensitive and accurate detection of various substances, from hormones to pathogens, providing crucial insights into a patient’s health status.

Antigens in Vaccine Development

Vaccines rely on introducing antigens to stimulate an immune response without causing the full-blown disease. This controlled exposure helps the immune system develop memory cells, ensuring future protection against the specific pathogen. The choice of antigen is crucial; it must be effective at eliciting a protective immune response without causing significant side effects. For example, the influenza vaccine typically contains inactivated or attenuated viral antigens.

These induce an immune response without causing the flu itself, thus protecting against future infections.

Antigens in Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy utilizes antigens to enhance or modify the immune response to combat diseases like cancer. Cancer cells often display unique antigens that differ from normal cells. By targeting these tumor-associated antigens (TAAs), the immune system can be trained to recognize and destroy cancer cells. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy is a prominent example. CARs are engineered receptors that allow T cells to recognize and attack cells expressing a specific antigen.

This approach is revolutionizing cancer treatment by harnessing the power of the immune system.

Antigens in Research and Drug Development

Antigens are fundamental tools in biological research and drug development. Researchers utilize them to study immune responses, identify novel drug targets, and evaluate the efficacy of potential treatments. Antigens can be used to create antibodies, which are then used to isolate and characterize various molecules. This information helps in designing targeted therapies and improving our understanding of complex biological processes.

For example, antigens are critical for understanding the intricacies of viral replication and designing antiviral drugs.

Applications of Antigen-Antibody Interactions

The specific interaction between antigens and antibodies is exploited in various medical settings. Blood typing, for example, relies on the interaction of specific antigens on red blood cells with antibodies in the recipient’s serum. This interaction determines compatibility for blood transfusions. Moreover, antigen-antibody reactions are essential in identifying pathogens and monitoring disease progression. The rapid diagnostic tests used to detect infections, such as strep throat, are based on these interactions.

Antigen Variation and Evolution

Antigens, the targets of our immune system, aren’t static. They are constantly evolving, a dynamic dance with our defenses. This ability to change shapes how pathogens interact with our bodies, and impacts the effectiveness of vaccines. Understanding these variations is crucial for predicting disease outbreaks and developing effective strategies for prevention.

Mechanisms of Antigen Variation, What is an antigen

Antigenic variation is the process by which pathogens alter their surface antigens, making them less recognizable to the immune system. This ability to evade the immune response is a key factor in the persistence and spread of infectious diseases. The driving force behind these changes is often genetic mutations, a cornerstone of evolutionary processes.

Role of Genetic Mutations in Antigen Variation

Genetic mutations are the primary engine driving antigen variation. These changes, often occurring in genes that code for surface proteins, can lead to subtle or dramatic alterations in the structure and function of the antigens. These alterations are not always detrimental to the pathogen. In fact, they can be beneficial, enabling the pathogen to evade the immune system and spread more efficiently.

Antigenic Drift and Shift

Antigenic drift and shift are two distinct mechanisms of variation observed primarily in influenza viruses. Antigenic drift describes gradual changes in the antigens over time, resulting from point mutations in the genes that code for surface proteins. Antigenic shift, on the other hand, is a more dramatic change, often involving the reassortment of gene segments between different influenza viruses.

This reassortment can introduce entirely new antigens to the human population, leading to pandemics.

Examples of Pathogens Exhibiting Antigenic Variation

Numerous pathogens exhibit antigenic variation. Influenza viruses, as mentioned earlier, are a prime example, with their frequent antigenic drift and occasional shift. Other notable examples include HIV, which mutates rapidly, making it challenging to develop effective vaccines. Certain bacteria, such asNeisseria gonorrhoeae*, also exhibit antigenic variation to evade the host’s immune response. Parasitic infections, such as malaria, also show significant antigen variation, posing challenges to both diagnosis and treatment.

Impact on Disease Transmission and Vaccine Effectiveness

Antigenic variation profoundly impacts disease transmission and vaccine effectiveness. The ability of pathogens to alter their antigens allows them to evade the immune response generated by previous infections or vaccinations. This means that vaccines that are effective against one strain of a pathogen might not be effective against another, requiring frequent updates to vaccines or alternative strategies to combat the pathogen.

This variability also contributes to the cyclical nature of many infectious diseases. For example, the seasonal nature of influenza outbreaks is largely attributed to the continuous antigenic drift of the virus. A vaccine designed to target a specific strain may become ineffective as the virus evolves.

Epilogue

In conclusion, antigens are more than just foreign invaders; they are the key players in our immune system’s intricate dance of recognition and response. From their structure and function to their role in disease and medical applications, we’ve explored the multifaceted nature of antigens. This discussion highlights the profound impact these molecules have on our health, immunity, and even the development of vaccines.

Further research into antigen variation and evolution will undoubtedly reveal even more fascinating aspects of this critical biological phenomenon.